My 2X-great uncle, Robert Franklin "Frank" Garner, was born in Friendship, Anne Arundel County MD, in 1862, the son of Robert Garner and Eleanor Maria Lyles. He joined the US Army in 1884 and died at Fort Leavenworth KS in 1904. In March 1900, a few months after his Army discharge, he married my 30-year-old 2X-great aunt, Lillian "Lily" Scrivener.

From the time of Frank's death in 1904 until her own death in 1948, Lillian Scrivener Garner struggled to obtain and maintain her right to a widow's pension for her husband's many years of military service. The pension file is a tribute to her dogged perseverance.

By the time he enlisted in the Army for the first time on 15 November 1884, both of Frank's parents were dead; he and his 14-year-old younger sister Harriet were living with their maternal aunt Harriet Lyles Pindell in New Jersey. 22-year-old Frank Garner, a clerk, was described as being 5'6" tall with gray eyes, dark hair, and a fair complexion. Frank subsequently re-upped in 1887, 1889, 1894, and 1897, and was honorably discharged in 1899 at Fort McHenry MD, reaching the rank of Sargeant Major having served in cavalry, artillery, and infantry units during his military career.

During his career, Frank worked as a clerk at various Army forts, mainly in the West, Fort Apache and Fort Grant in Arizona, Fort McIntosh TX, and Angel Island CA, among others. He served in two different wars--the Indian Wars in the 1880's and the Spanish-American War in 1898. After his discharge, he went to work for the Army as a clerk at Fort Leavenworth, where he died of pneumonia in March 1904.

|

| Geronimo 1887 |

In a letter from Fort Apache to his Aunt Bettie (Elizabeth Smith Garner) in January 1885 (included in the pension file to prove his service in the Indian Wars), Frank says that he is in "[Apache Chief] Geronimo's stomping grounds." Although he spends most of his time in an office with very little field duty, he indicates that he doesn't like the "vicious" Indians at all, repeating the meme that "the only good Indian is a dead Indian."

|

| Lily Garner and Eleanor |

The Scriveners and the Barbers were neighbors of the Garners in southern Anne Arundel County; Lily's Uncle Jonathan Barber married Frank's Aunt Jennie Garner and Lily's uncle James Scrivener married Frank's Aunt Kate Garner. So, I am fairly sure that Lily and Frank met through a family connection.

They were married at St. Michael and All Angels Church in Baltimore MD after Frank's discharge from the Army. Their only child, Eleanor McPherson Garner, was born at the home of her Scrivener grandparents on 14 March 1901.

According to Lily's pension file, she and her daughter lived with Frank at Fort Leavenworth until Eleanor, who was apparently a delicate child, became ill and the doctor advised taking her to a friendlier climate. Lily and Eleanor moved back to Maryland and stayed with Lily's mother until the little girl regained her strength. I think the picture above was probably taken to send back to Frank as a reminder of his family.

Lily applied for a widow's pension in May 1904, within a couple of months of Frank's death, but her application was rejected. After an exhaustive review of every medical treatment Frank had received (documented in excruciating detail in the pension file), the Pension Bureau denied Lily's claim because Frank's death occurred more than five years after his discharge, and his death from pneumonia was not related to his military service. She was rejected again in 1909 for the same reason.

Nevertheless, she persisted. Fortunately for her, Congress periodically changes the parameters of pension funding. So, enlisting the aid of her cousin, Rep. Frank Owens Smith, Lily got a special act of Congress to add her to the pension rolls in July 1914, ten years after Frank's death, based on his service in the Spanish-American War. She was awarded a pension of $12 per month plus an $2 per month for her daughter Eleanor until the girl turned 16. Even then, she didn't get any payment until several months later when she had documented the exact date of birth of her daughter by the affidavit of her sisters, Sallie and Leila.

You might think that that Act of Congress would solve Lily's pension problem, but you would be wrong. Lily had to keep up constant vigilance to maintain and protect her pension.

A few months after the initial pension grant, in March of 1915, Lily wrote a letter to President Woodrow Wilson, asking that she receive the back payments of her pension to which she felt she was entitled. Her letter, included in the pension file, told a heart-breaking story. Since my husband's death, she said, "I have had to work very hard running a rooming house to earn a living for myself and my little girl trying to send her to school." But, she noted, her health had finally forced her to give that up and she was at the time "strapped down to an iron frame at Church Home Hospital with tuberculosis of the spine." That back payment, Lily told the president, would help to prolong her life. Her request did get reviewed but was rejected.

By 1917, however, the rules had changed again, and her pension was increased to $25 per month. By 1926, a new act of Congress increased it to $30 per month.

However, a cost-cutting move by Congress in 1933, cut her pension in half to $15 per month. This time Lily enlisted the help of her Senator, Millard Tydings. "I am way up in my sixties," she told Tydings, "unable to move around much, as I unfortunately had a broken vertebra in my spine sometime back, unfitting me for anything." Her pension, she reminded him, was her "only dependence," except for a few dollars she was able to raise by darning socks for some of the gentlemen in her apartment building. Her relatives, she told him, were no longer able to help her as they faced health issues and fall-out from the Great Depression themselves. "What can I do with only $15 a month?"

The Army's director of pensions responded to Senator Tydings several months later, confirming that her pension was indeed cut down to $15 and could not be increased. But, he noted, there was a higher rate of pension granted to certain widows of soldiers who served in the Indian campaigns, which, of course, Frank Garner had. He advised that Lily was welcome to pursue that option if she so desired. (A widow could not get a pension from more than war at a time, and different wars had different pension rules. Of course they did.) She submitted a new application as well as several letters that Frank had written to family members (like the one to Aunt Bettie, above) as proof of his service.

In January 1934, she was awarded a new pension of $30 per month based on Frank's Indian War service. However, the first check was for only $27, which worried her enough to write back to the pension office. Congress, it turned out, had already cut the pensions by 10% across the board.

Ten years later in 1944, the eagle-eyed Lily spotted this story in the Sun:

She promptly wrote to the Pension Bureau to switch back to a Spanish War pension at the increased rate of $40, which was eventually approved several months later.

Sadly, two years later in 1946, Lillian Garner was declared incompetent to manage her affairs and was committed to the Springfield State Hospital. The Union Trust Bank was appointed as Trustee to manage her pension.

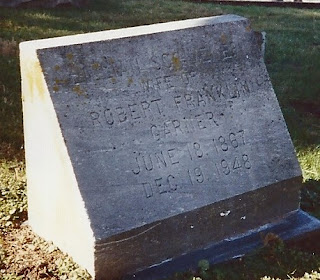

Lillian is buried at St. James Church in Lothian, Anne Arundel County MD, near her brother and her Garner in-laws.

Now, the question that occurred to me throughout my reading of Lily's pension saga was this: Where the heck was Eleanor all this time?

I happen to know from previous research that Eleanor McPherson Garner was a wealthy woman, having married in succession four very well-to-do men, starting with Baltimore playboy Gilbert Lucas in 1923. And that is a whole other story, which you can see here.

While Lily struggled with ill-health and a miniscule pension, her daughter was living the high life in New York, Chicago, Miami and Paris, among other hot spots in the US and Europe. When her mother was committed to a state hospital and died of cancer a few years later, Eleanor was living in a fashionable Manhattan apartment recovering from her fourth divorce.

Wasn't there something Eleanor could have done to help Lily? Nothing in the pension file about that.

Quite a tribute to a strong woman. Even an Act of Congress didn't do the trick? I'd want Lillian fighting on my behalf.

ReplyDeleteWhat a battle! I had one ancestor whose wife was denied a pension because they married after his service. Another, who was almost 100, was denied because there were no living witnesses to her husband's service! Great story!

ReplyDeleteWow. What a story of perseverance!

ReplyDelete