Baltimore, Maryland is my hometown. I was born there at Mercy Hospital in 1948. But long before I showed up, many of my Scrivener ancestors had called this city home. My 3X great-grandfather, Benjamin Gaither Keene, moved from Dorchester County on the Eastern Shore of Maryland to Baltimore about 1860 and died there in 1865. He and his wife, Susan Tubman McMullan, were buried in the cathedral cemetery. Their daughter, Marie Louise Keene, married my 2X great-grandfather, Andrew Jackson Gwynn, in the Baltimore Basilica in 1868.

|

| Mt. Saint Agnes |

Even though the Gwynns spent most of their married life in Spartanburg SC, they sent their daughter, Louise Carmelite Keene Gwynn, back to Baltimore for her education at Mount St. Agnes College, opened by the Sisters of Mercy in 1890 in the Mount Washington area of Baltimore.

My great-grandfather, Frank Phillip Scrivener, was born in Anne Arundel County MD in 1865 and educated at Glenwood Academy in Howard County MD (where he won the gold medal for Mathematics in 1881). By 1896, he and his two youngest brothers Jonathan and Kent, were living in Baltimore. Frank was an accountant for the Joseph Gottschalk Company, a well-known importer and distiller of fine liquors with its own distillery at North Saratoga Street, specializing in Maryland Rye. Frank worked for Gottschalk until his retirement in 1928. |

| Gottschalk Distillery |

I would like to show a little of the Baltimore that Frank and Louise and their son, Frank Jr., would have known during their 30 years in the city.

After the Civil War, Baltimore industry gathered momentum. The city's connections to the Bay’s fishing industry and the fertile farmland around the Chesapeake Bay helped to concentrate canning factories around the harbor’s edge.

In fact, by the 1880s, Baltimore had become the world’s largest oyster supplier and America’s leader in canned fruits and vegetables. In addition, Baltimore was America’s ready-made garment manufacturing center and

the world’s largest producer of

umbrellas. More than two million immigrants landed first in Fells Point and

then in Locust Point, making the

City second only to New York as an

immigrant port-of-entry. Most new

arrivals promptly boarded the B&O

Railroad and headed west, but many stayed to create a colorful tapestry of vibrant and diverse neighborhoods.

|

| City Hall 1873 |

While horsecars and later trollies expanded Baltimore’s physical reach, steamships and railroads tied Baltimore to the global economy. The B&O Railroad connected

Baltimore to the West; the Philadelphia, Wilmington and Baltimore Railroad

connected the City to Philadelphia; and the Maryland and Potomac Railroad connected Baltimore to the South.

As of 1893, Baltimore had more millionaire philanthropists than any other

city in America; moreover, through the benevolence of four Baltimoreans,

modern philanthropy began.

In 1866 the Peabody Institute opened with a music school, an art gallery, a lyceum, and a library more comprehensive than the Library of Congress.

|

| Peabody Library |

|

| Pratt Library Mulberry St. |

William Walters and his son Henry Walters founded the Walters Art Gallery in their Mt. Vernon home in the late 19th century and about 1905 added an elaborate stone pallazo-style structure in order to allow the public to view their collection. At his death in 1931, Henry bequeathed the entire collection of more than 22,000 objects plus his home and gallery to the city of Baltimore.

Wealthy merchant Johns Hopkins envisioned his legacy as a hospital and medical school tied to a university, a radical idea in the late 19th-century that later became the model for virtually all academic medical institutions. At his death in 1873, he left a bequest of $7 million to the university and hospital that would bear his name. At the time, it was the largest philanthropic bequest in American history. The hospital, completed in 1889, was considered the largest medical facility in the country with 17 buildings, 330 beds, 25 physicians and 200 employees.

|

| Penn Station 1911 |

After the Great Fire of 1904, which fortunately for the Scriveners did not reach their part of the city (See The Scriveners and the Great Fire of Baltimore), the downtown smoldered for weeks. The

fire consumed 140 acres, destroyed 1,526 buildings, and burned out 2,500

companies.

Baltimore quickly began rebuilding, and dozens of buildings were being

constructed a year later. Ten years after the fire, Baltimore’s downtown was

completely rebuilt. In all, the fire made way for several significant improvements to the downtown: twelve streets were widened, utilities were moved

underground, a plaza was established, and wharves were rebuilt and became

publicly owned. The fire also led to stricter fire codes for Baltimore and national standardization of fire hydrants and fire-hose connectors.

The drawing below shows a birds-eye view of the city in 1911 about 7 years after the Great Fire of 1904. This is the Baltimore that the Scriveners would have known, a city of about 500, 000, the sixth largest city in the country. Democrat James H. Preston was mayor from 1911 to 1919.

|

| Emerson (Bromo-Seltzer) Tower |

Toward the upper middle of the drawing, you can pick out the famed Washington Monument at Mount Vernon Square, which has graced the Baltimore skyline since 1815, the first monument to honor George Washington. It was designed by American architect Robert Mills, who later went on to design that other monument in the District of Columbia.

And if you really squint, you might pick out the Beaux-Art bulk of Penn Station (then known as Union Station) in the far north distance, newly opened in 1911.

Frank and Louise lived at 105 E. Lafayette Avenue, near Green Mount Cemetery and a few blocks from Penn Station. I have marked the approximate location on this contemporary map, north of the Bromo Seltzer Tower and the Washington Monument.

Here is a picture of Louise with her only son, Frank Jr., in front of their house in1901. Notice the classic white marble steps/stoop typical of Baltimore. Upon their installation in the 1900’s, white marble steps were felt to add an instant element of class and swankiness to otherwise working-class homes. Housewives would scrub the steps every weekend to keep them gleaming. It's likely that Louise and Frank joined their neighbors in a little stoop-sitting in the humid Baltimore evenings.

I also have another picture that shows a little of the interior of the Scriveners' home, decorated in a typical Victorian style and crammed with pictures and knick-knacks. That dresser against the wall is still in the family.

The house at 105 is no longer standing, but here is a contemporary picture of its near neighbors in the 100-block of East Lafayette, so you can get a little feel for the style of the classic Baltimore row house. This block is a little more upscale that some of the working-class neighborhoods where the houses were just four rooms. The Scriveners' home was three stories in height and three bays wide. They had a first-floor parlor with a side hall, backed by a dining room, with two bedrooms above. A narrow rear wing provided space for the kitchen on the first floor and more bedrooms on the second and third floors. Every room had at least one window—except the bathroom, which usually made do with a skylight. In row houses of all sizes, front doors are dauntingly narrow. An alley usually ran behind the row of houses to provide service access.

Apart from the monuments and public buildings, Baltimore also provided the amenities of ordinary life for the Scriveners, schools, churches, markets.

Although they may have attended some special services at the Basilica of the Assumption, Baltimore'sCathedral, the Scriveners' regular parish was St. Ann's on Green Mount Avenue, a few blocks from their home. Frank Scrivener Sr., raised in the Anglican Church, was baptized a Catholic at St. Ann's Church in 1905. Louise Gwynn was a devout Catholic. St. Ann's was established in 1872 by a generous donation from William Kennedy, captain of one of Baltimore's famous Clipper ships. Caught in a raging storm off Vera Cruz, Kennedy vowed that if his anchor held, he would build a church in thanksgiving. He made it safely back to Baltimore and kept his vow, naming the church after St. Ann, patron of sailors. The anchor from his clipper ship still stands next to the cornerstone of the church.

Baltimore's Lexington Market, founded in 1782, is America's oldest market, built on land donated by Revolutionary War General John Eager Howard. By the mid-19th century, it was unquestionably the largest, most famous market on earth. When Ralph Waldo Emerson visited the market, he proclaimed Baltimore "the gastronomic capital of the world." By 1925, there were over 1000 stalls in 3 block-long sheds. Anything Louise and Frank might have needed in the way of food was available just a few blocks from their home.

The Baltimore Polytechnic Institute, where my grandfather Frank Scrivener Jr. attended school, was founded in 1883. By 1913, the school had relocated to a site a few blocks from the Scriveners' home. Poly was considered one of the country's outstanding engineering high schools and Frank went on to a distinguished career as a highway engineer.

|

| Baltimore Zoo at Druid Hill |

|

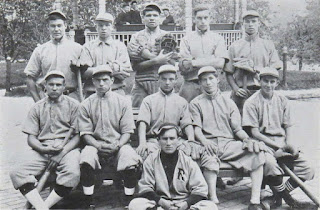

| Babe Ruth's team at St. Mary's 1914 |

At St. Mary's Industrial School, George found his passion for baseball and was offered a contract by the Baltimore Orioles in 1914, at the same time acquiring his nickname, Babe, in reference to his youthful appearance.

|

| Frank Scrivener Jr. 1908 |

The Baltimore that the Scriveners knew was a thriving, dynamic city that offered its residents a wealth of opportunities and amenities.

No comments:

Post a Comment