Now I'm looking at a different aspect of that experience: the connections among the soldiers in his company.

John Scrivener served in the 2nd Regiment of the Maryland militia, the company headed by Captain Thomas Tillard Simmons, from about April 1813 to November 1814.

I was able to identify a little over 90 men who served at various times in his unit, all from the general area of Friendship, in southern Anne Arundel County and northern Calvert County. Look at the Census rolls for 1800 and 1810 and 1820, and you will find these same men living side by side. Most of the men were in their twenties and thirties, as you might expect for soldiers, but there were a few older men. The company also included two Negroes, Nace Butter and Nathan Pherson, the fifer and drummer, respectively. They were the servants of Lt. Scrivener and Captain Simmons (not clear if these men were enslaved or free).

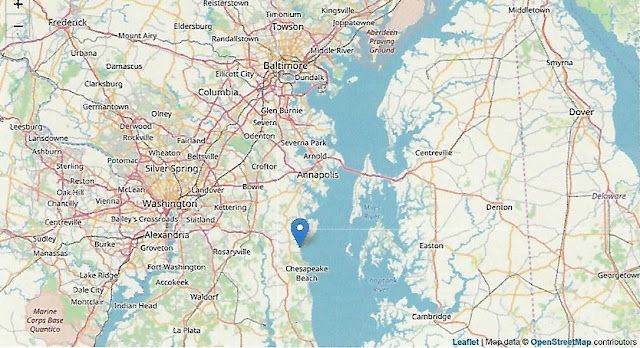

These men were not full-time soldiers. The company was mostly called out when British ships were spotted in Herring Bay or making their way toward Baltimore: "An English ship and brig laying off Herring Bay was the cause of my ordering out my company." The location of this company made it perfect for spotting British ships and preventing their landing. See map below. On a few occasions, some of the men were sent to Baltimore, and a few helped in the defense of Fort McHenry, although that was not their usual duty.

When I started looking at the men as a group, I discovered that they were connected by a whole web of relationships besides their military status and the geographic proximity of their homes. The men in Captain Simmons' company fought alongside their fathers, fathers-in-law, brothers, brothers-in-law, cousins of various degrees, nephews, uncles, sons and sons-in-law. Any injury or death in this company was not just a strategic loss but a very personal loss.

Here are a few of the examples of the relationships I found.

|

| Brothers |

There were at least four sets of brothers in the company, including John Scrivener and his younger brother Francis, about whom I have written previously. There were five Ward men in this company: William, Richard, Robert, Samuel, and John, all the sons of Robert and Sarah Ward. The Whittington family contributed three brothers: Francis, Benjamin and Charles, the sons of Francis Whittington Sr. Plus there were a couple of Whittington cousins: John A. Whittington, William Whittington and Richard Turner. Two of the oldest men in the group were brothers Samuel and Henry Wood, 60 and 40 years old respectively, both sons of William Wood.

There were also several Hardesty men--Benjamin, William, and Joshua--that I strongly suspect were brothers, but I haven't found the evidence to back up that suspicion, yet.

Unfortunately, there aren't any photos from 1814, but I'm sure these brothers were just as cute as the two at the right, to their mothers, anyway.

Captain Thomas Simmons, the son of Abraham Simmons and Priscilla Lyles, was serving with his cousin Isaac Simmons, the founder of the town of Friendship. His unit also included his brother-in-law, Joseph G. Harrison, the brother of his wife Ann Harrison, as well as his future son-in-law, John Wood, who married his daughter Eleanor Lyles Simmons in 1818. John was also the executor of Captain Simmons' estate when he died in 1832. John Wood's second wife, by the way, was Sarah Ward, a cousin of the Ward brothers, above.

Lt. John Scrivener, besides serving with his brother Francis, was also serving with his brother-in-law, William Ward, who married his sister, Sarah Scrivener. The Whittington brothers above, were the nephews of John and Francis's stepmother, Eleanor Ward Scrivener. John A. Whittington was the stepson of John and Francis's sister, Elizabeth Scrivener Whittington.

Samuel Stevens' mother was Lavinia Whittington, the aunt of the three Whittington brothers, above, making them first cousins of Samuel. Joshua Hardesty's mother-in-law, Araminta Wood, was Samuel Stevens aunt.

Dr. Walter Wyvill married Ann Wood, the daughter of Samuel Wood, above. Dr. Wyvill's half-sister, Eleanor Wyvill Connor, was the mother-in-law of Sabrett Trott.

Samuel Gover was a trustee of the Friendship Methodist Episcopal Church, along with Lt. John Scrivener. He married Sarah Ann Hardesty, a cousin of the Hardesty's above.

Walter Carr married Mary Scrivener, a cousin of John and Francis.

William Sullivan, the son of Thomas Sullivan and Sarah Wood, was the nephew of Samuel and Henry Wood, above.

Joseph G. Harrison married the sister of John Wood, Matilda Burgess Wood and his sister, Ann Harrison, was the second wife of Captain Simmons.

Even when the war was over, the men supported each other. When the US authorized bounty land and later pensions for service in the War of 1812, the applications required witnesses who could verify the service of the applicant and vouchsafe that the applicant was, in fact, who he said he was. When Richard Ward died, for example, his fellow soldier William Hardesty represented his children in applying for their father's pension in 1855. Two other men from Simmons' company, Samuel Gover and Richard Griffith, supported his application. When Samuel Gover applied for his pension, John Scrivener's son William Boswell Scrivener, supported his application.

In addition, these men often witnessed each other's wills and land deeds and served as bonds for the administration of estates.

These are just a few examples of the complex web of relationships I found among the men who served in Captain Thomas Simmons' company. I'm sure if I worked on it long enough, I could make a connection for just about every man with at least one other member of this unit. These citizen-soldiers were not professional military men. They served for days or weeks at a time when they were called upon, but in between they went back to their regular work of farming or managing a store or caring for sick patients and raising their families.

Captain Simmons' men were not strangers thrown together in battle; the men in the militia unit were neighbors and family, people who shared their everyday lives, not just their lives as soldiers. These people went to each other's weddings and funerals, attended the same schools and churches, gathered for family dinners together, complained about the weather and the stupid politicians, and the decline of the younger generation. Many of these men lie buried together at Friendship United Methodist Church Cemetery.

I know these relationships must have made a difference in how these men experienced the war.

No comments:

Post a Comment